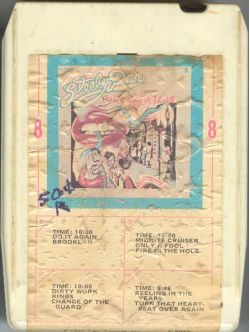

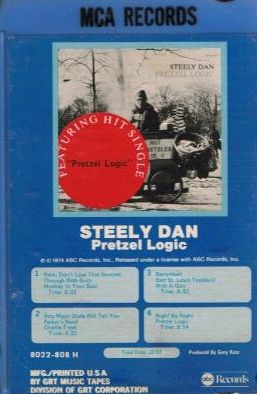

I’m not sure why, but certain major labels in the seventies and eighties would release cassette and vinyl versions of specific albums with different song sequences. The three I remember clearest from the seventies are Steely Dan’s Pretzel Logic and Can’t Buy a Thrill as well as Cheap Trick’s Heaven Tonight. Did these differences have to do with space restrictions from format to format? Maybe, but I’m not convinced. I bring this up is because I lament how Steely Dan’s Pretzel Logic now survives only in the original vinyl sequence, and I want more listeners to consider experiencing it in the more meaningful sequence used on the original cassettes. Let’s compare the two:

Steely Dan, Pretzel Logic (LP version): Side One – 1) Rikki Don’t Lose That Number; 2) Night By Night; 3) Any Major Dude Will Tell You; 4) Barrytown; 5) East St. Louis Toodle-Oo. Side Two – 1) Parker’s Band; 2) Through with Buzz; 3) Pretzel Logic; 4) With a Gun; 5) Charlie Freak; 6) Monkey in Your Soul.

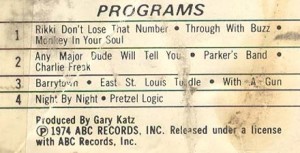

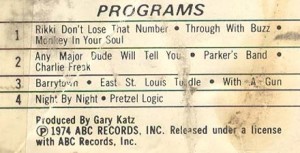

Steely Dan, Pretzel Logic (cassette versions): Side One – 1) Rikki Don’t Lose That Number; 2) Through with Buzz; 3) Monkey in Your Soul; 4) Any Major Dude Will Tell You; 5) Parker’s Band; 6) Charlie Freak. Side Two – 1) Barrytown; 2) East St. Louis Toodle-Oo; 3) With a Gun; 4) Night By Night; 5) Pretzel Logic.

On the vinyl version, two of the album’s most crescendo-worthy cuts, the neon-lit “Night By Night” and “Pretzel Logic,” with its epic mad visions, are squandered off in the middle of sides one and two, respectively. On the cassette version, they close the album effectively, one after the other with the same sort of authoritative finality as nightfall and dreams.

Sides one and two of the vinyl version end with what come off as offhanded snickers – “East St. Louis Toodle-Oo” and “Monkey in Your Soul.” On the cassette version, though, they’re rightfully reconfigured as supportive – and therefore more useful – middle tracks, giving way to the haunting and poignant “Charlie Freak” as the side one closer and “Pretzel Logic” for side two.

The entire trajectory of the album, in fact, makes more sense in the cassette versions. Let me rephrase that: it makes sense while the vinyl one doesn’t. Side one of the cassette functions as a series of person-to-person conversations, pleas, jokes, and negotiations, all of which give listeners a sense of the tangled, “pretzel”-like nature of relationships. “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number,” that vulnerable and familiar message to a girl we all assume the singer will never hear from, is followed up by his declaration of having had it with a pain-in-the-neck friend named Buzz who steals girlfriends (Rikki?) and money. Next comes “Monkey in Your Soul,” which offers classic Steely Dan yuks by featuring a prominent, buzzing guitar line as a follow up to a song called “Through with Buzz.” It also reinforces the “yeah, right” nature of “Monkey’s” message which is that, no, the singer can’t hold his ground. He can only supplicate, wise-crack, or grouse. “Any Major Dude Will Tell You” reinforces our impression of him – all nifty words and no action – and we feel pity. With “Parker’s Band,” our frustrated singer is listening to records and longing to get lost in the city where he can lead a loose and commitment-free existence, something he’ll actually gun for in response to the tragic side one culmination of “Charlie Freak.” There’s no second-person dialogue going on in this song. Someone’s dead now, and the best our man can do is drop a keepsake in the corpse’s coffin. Time to make some changes.

Side two of Pretzel Logic, as conveyed so well in the cassette sequence, elaborates on the nightlife fantasies we heard about in “Parker’s Band,” conjured up by the interpersonal failures in side one. It’s about foregoing the micro-existence of relationships and losing oneself in the impersonal, macro-existence of the “city.” It kicks off with “Barrytown,” Steely Dan’s own twisted version of “Okie from Muskogee,” calling for the removal of people like the singer in side one from where folks like to do things the old-fashioned way. This is followed up by city-life objectification and fantasy with a version of Duke Ellington’s “East St. Louis Toodle-Oo,” which serves as a symbolic gateway. Fantasy gives way to reality with the scenes of murder and robbery in “With a Gun,” with its campy steel guitars channeled in directly from Muskogee. But this is general street conflict nowhere near as painful as the heartbreaking business documented on side one, and on the following track we see our singer-protagonist reveling and taking refuge in it, living “night by night.” It’s a moment of bittersweet transcendence that Joe Jackson later tried to capture in “Stepping Out” as the “night” side closer for his carefully sequenced Night and Day LP. (It’s no surprise that Jackson was a huge Steely Dan fan, something we find out in his A Cure for Gravity. I’ll bet he owned the cassette version of Pretzel Logic – not the vinyl.) With “Pretzel Logic,” finally, we get a cinematic escape into dreams, time-travel and absurdity, providing the whole story, in conclusion, with an apt title.

Bud Scoppa’s 1974 review of Pretzel Logic in Rolling Stone sums up how the album, in its vinyl sequence, has continued to be understood as merely a collection of cleverly executed songs: “wonderfully fluid ensemble. . . private-joke obscurities. . . arrogant impenetrability.” The cassette version, though, which someone with some authority arranged in a distinctly different sequence, sounds like a carefully constructed album with an actual story to tell.