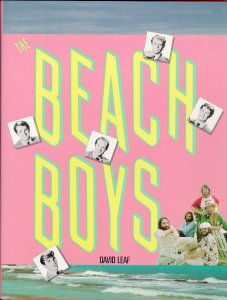

David Leaf, now a successful TV writer, producer, and film director, is the senior caretaker of the Beach Boy narrative, and his The Beach Boys and the California Myth (1978) was the first substantial book about the group. It’s well worth digging up (a must if you’re a Brian Wilson cultist) but you might have to get it from your library since it’s never in print and goes for spirit-crushing prices on eBay. Or look in used bookstores for the potentially less expensive second edition (and, to date, latest), which came out in 1985 and is jam packed with essential “codettas” by the author. Simply called The Beach Boys (pictured above), you might mistake it for a coffee table fluff job, with its 80’s flamingo dust sleeve and thin, longish size, but don’t be tricked. Grab it if you see it (I found mine that way for $9.98, but that was around ten years ago).

Leaf admits to having found the inspiration to tackle his subject after reading Tom Nolan and David Felton’s seminal two-part 1971 article on the Beach Boys in Rolling Stone. By the mid-seventies, Leaf had packed his bags and moved from the East coast to the West and lost himself in his passion – the music of Brian Wilson – and churned out one of the finest bits of “advocacy journalism” (Leaf himself refers to it as this) one is likely to read in the discombobulated realm of pop music literature. “This book is written for one man, Brian Wilson,” Leaf writes in his intro, and so unwavering is he in spelling out the painful details of what he considers to be “ultimately a tragic story,” that anyone who reads his book from cover to cover will realize that he ought to have just called it “Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys Myth.”

Indeed, the overarching theme here is that Wilson’s loyalty to his family and the Beach Boys franchise – both of whom clearly feared any deviation from the successful hitmaking formula Wilson had mastered from ’61 to ’66 as a dangerous financial risk – was killing him artistically. There lay the blame for the collapse of Smile and God knows what else Wilson may have had brewing. Leaf never loses sight of just how insurmountable this great obstacle in Brian’s artistic life seemed, but he also never refrains from making clear his view that “an artist must put aside obligations to family and friends; he must put his art and himself first.” (Even Eugene Landy, the now discredited therapist, is treated with suspicion by a tuned-in Leaf circa ’85 for offering Wilson precious little in the way of artistic freedom.) This angle of Leaf’s, in fact – of the artist/idealist manacled to family expectations and commerce – is certainly as quintessentially American and epic (and at least twice as tragic) as the “California myth” we’re all too familiar with.

There are three other glorious aspects worth mentioning about the ’85 edition of this book: 1) We get to read about the after effects of its publication, most notably the fact that it earned Leaf Wilson’s trust to the extent that he was admitted into the master’s inner sanctum and that it provoked the apparently ever-smoldering anger of the misnamed dullard we know as Mike Love; 2) we are assured that Leaf is such a true believer in Brian Wilson’s musical gifts that he was able to write, even in the retrospectively cloudy days of “Getcha Back,” that “I’m part of a small cult that has complete faith that the creative resurrection of Brian is imminent”; and 3) we are now able to read it with the glad knowledge that Leaf, who believed then that “a collection of [Smile‘s] still-unreleased fragments pieced together with the music that has come out would make for an unparalleled collection of pop music experimentation,” has not only seen its improbable release, but he also ended up making the documentary.