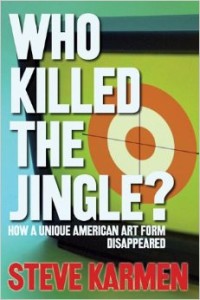

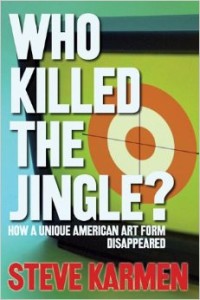

Curiosity about the Budweiser and Pontiac jingles I’d written about earlier led me toward composer Steve Karmen’s book Who Killed the Jingle?: How a Unique American Art Form Disappeared (2005). I approached this expecting Karmen – who wrote hundreds of ad jingles, many of which you’d instantly recognize – to attempt to explain how the end of his own career equaled the end of good advertising.

Curiosity about the Budweiser and Pontiac jingles I’d written about earlier led me toward composer Steve Karmen’s book Who Killed the Jingle?: How a Unique American Art Form Disappeared (2005). I approached this expecting Karmen – who wrote hundreds of ad jingles, many of which you’d instantly recognize – to attempt to explain how the end of his own career equaled the end of good advertising.

In fact, Karmen demonstrates quite convincingly how this was actually the case: his own legal efforts to strengthen the financial future for ad composers in the present, where unique content routinely gets passed over in favor of recycled pop songs, really did have implications for his trade. Karmen was one of the very few jingle writers who has managed to retain his own publishing rights and, therefore, the proud sense of legal ownership for his work normally afforded to pop songwriters, and he advocated for this on behalf of all jingle writers.

In Who Killed the Jingle?, then, Karmen details his failed attempts as Chairman of the now-defunct Society of Advertising Producers, Arrangers and Composers (SAMPAC) to challenge the payment scale adhered to by the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP). This is the original performance rights organization, formed in 1914, which favored – then as now – the same pop songwriters who invented it, giving themselves sacred protections forbidden to the vermin who wrote for the not yet fully understood media of TV, movies, or radio. For these folks, the quick payout and relinquishment of ownership rights was, and continues to be, a standard expectation.

One of Karmen’s key hardships, apparently, was an inability to rally the troops in a way that inspired them to envision a future in which a classic jingle, like Karmen’s own “When You Say Bud” or “I Love New York,” could bring its writer ongoing financial rewards. What has this situation led to? An advertising world in which the traditional songwriting industry has swallowed up everything. Pre-existing pop songs now sell products, and ad agencies hunt for them with sizzling hot branding irons.

Gone are the days, in Karmen’s words, of “custom-made music and lyrics for advertising.” Because my own father was a regional jingle writer, whose work put food on the table, my own loathing for the current state of advertising perhaps runs a bit high. Maybe the sick feeling I get when I hear a pop song on a commercial is just a psychological response to the devaluation of the jingle writer.

But I do believe, like Karmen, that advertising was a more creative industry before song licensing became the norm. It’s a practice that “exhibits nothing more,” as he puts it, “than a profound lack of imagination.” Would I have an easier time with all media if the advertising they feed on were more straight up? Karmen’s book has me thinking that I would, which is a surprising admission, but I think it beats the current, sneak-attack approach, which succeeds only in appearing sneaky. Like Karmen, I feel advertising should “go back” to “what it once was. Honest. And entertaining.”

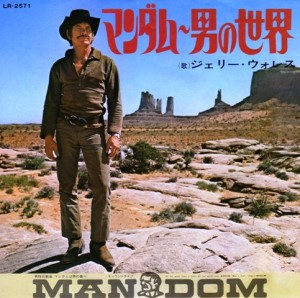

A curious addition to the country pop singer Jerry Wallace’s resume: The biggest selling single of his career was a 1970 Japan-only release that featured Charles Bronson on the sleeve. It was the soundtrack to a commercial for an aftershave called “Mandom,” starring Bronson as an urbane action figure who rewards himself at night by splashing the product all over himself like victory champagne. As he does this, Wallace gives the following lyrics one hundred-and-ten percent: “All the world loves a lover/All the girls in every land-om/And to know the joy of loving/Is to live in the world of Mandom.”

A curious addition to the country pop singer Jerry Wallace’s resume: The biggest selling single of his career was a 1970 Japan-only release that featured Charles Bronson on the sleeve. It was the soundtrack to a commercial for an aftershave called “Mandom,” starring Bronson as an urbane action figure who rewards himself at night by splashing the product all over himself like victory champagne. As he does this, Wallace gives the following lyrics one hundred-and-ten percent: “All the world loves a lover/All the girls in every land-om/And to know the joy of loving/Is to live in the world of Mandom.”